In a recent publication, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York took up the question: ‘Do the Benefits of College Still Outweigh the Costs?’ The report, which attracted the interest of several mainstream news organizations, noted that, at the end of 2013, aggregate student debt in the United States exceeded $1 trillion, and more than 11% of student loan balances are either delinquent or in default. These unfortunate facts, however, do not vitiate the welcome finding that the college degree has maintained a steady ROI of 15%, which, the authors note, ‘easily surpasses the threshold for a sound investment’. Granted, this 15% has held steady only because the wages of people without college degrees have been falling faster than the wages of college graduates. But these unfortunate social facts are irrelevant to the concept of a sound investment in any case. The authors do go on to caution, however, that ‘while the benefits of college still outweigh the costs on average, not all college degrees are an equally good investment’.

The corporatization of the university in recent decades cannot be understood in isolation from neoliberalism’s general assault on public values, public goods, and public service. It belongs alongside the effort to gut or privatize social insurance programs like social security (legacies of the now long-dead social citizenship state), attempts to abolish welfare or turn it into a form of work discipline, and the broader dismantling of public spaces where people meet to do things other than shop and consume. The relentless market logic of neoliberalism continues to hammer away at the sorry remains of non-commodified study and research still left in the university today. Protests erupted in March this year at the University of Southern Maine, after it was announced that a number of institutions in the University of Maine System would be laying off about 165 faculty and staff members. Inside Higher Ed reported that ‘the brunt of the cuts appear to be falling on liberal arts professors.’ A UMS economist noted that ‘A university that doesn’t have a robust core of liberal arts isn’t a university, it’s a trade school.’ These thoughts were echoed by a student leader of the protests, who said ‘And what I see happening is people being told that they can no longer have a humanities education here, they can no longer have a thriving social sciences department.’. Another way of marginalizing the social sciences and humanities can be discerned in ‘NY SUNY 2020’, a plan passed by the New York State legislature in 2011 that replaces public education with the idea of ‘public-private’ partnerships, where universities in the SUNY system compete for Challenge Grants on the basis of their ability to attract private funding. Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences are likely to be under even more pressure to cut programs, salaries, and personnel. Meanwhile, in February, a new form of privatization emerged as the Pennsylvania legislature began working on plans to allow individual universities to ‘secede’ from the state system. By seceding, a college can get out of its obligation in state law to ‘provide high quality education at the lowest possible cost to students’. Freed from that obligation, the colleges can of course get on with the real business of attracting private funding.

The aggressive marginalization of the arts, social sciences and humanities in the neoliberal university is a direct consequence of the understanding of a college education as a personal investment, undertaken by the student, and by which he or she consumes educational services in order to build educational capital. In the neoliberal order, departments and specialties that are not able to sustain themselves as self-governing profit centers are destined to be dismantled.

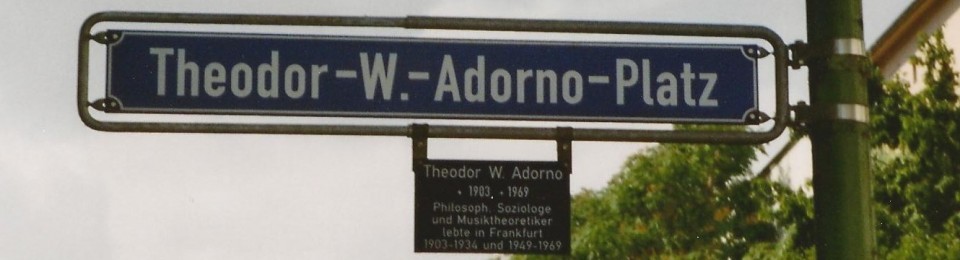

In such a hostile environment, how does one go about defending these obsolete remains of a world when universities were, to a degree, something more than high-end shopping malls, renting out their ‘labs’ to faculty who bring in the money? The first task, I want to suggest in this post, is to be clear on what it is about the humanities and social sciences that renders them obsolete in the neoliberal model of education. Theodor Adorno died before witnessing the full flowering of neoliberalism, but his reflections on education are invaluable for understanding the deeper nature of the conflict. Adorno helps us understand why the social sciences and humanities are capable of resisting commodification and hence why, from the neoliberal perspective, their value is always suspect. In the essay ‘Philosophy and Teachers’, Adorno writes that what makes someone an intellectual is not merely the possession of specialized knowledge. Rather, it is ‘manifested above all in his relationship to his own work and to the societal totality of which it is a part’.[1] While Adorno is here criticizing the technocratic consequences of disciplinary specialization, it isn’t too difficult to see that the same argument is also going to skewer contemporary processes of rampant commercialization and commodification. Adorno often refers to what is left out by (in his day) prevailing practices of education as ‘spirit’. In ‘Note on Human Science and Culture’, for instance, Adorno asks whether students can still gain the ‘spiritual experience’ that inheres in the concept of human culture.[2] Spirit cannot be commodified because its value is irreducibly public, and irreducibly social. Its riches are not amenable to a logic of investment because they do not inflate the private self with marketable skills. Instead, they seek to transform the private self through helping it to understanding its relationship to the social totality.

We can get a clearer sense of what Adorno is talking about from Henry Giroux’s discussion of the ‘new illiteracy’ promoted by American educational institutions

Illiterate in this instance refers to the inability on the part of much of the American public to grasp private troubles and the meaning of the self in relation to larger public problems and social relations. It is a form of illiteracy that points less to the lack of technical skills and the absence of certain competencies that to a deficit in the realm of politics.

This, Giroux notes, is a ‘civic illiteracy’ in which ‘it becomes increasingly impossible to connect the everyday problems people face with larger social forces’. This tendency is everywhere, from pharmaceutical companies urging pills as solutions to life’s problems, to the self-help books pushing positive thinking as a solution to poverty, to the reductio ad absurdum of private solutions to social problems: bullet-proof school supplies for kids as a solution to gun violence.

It is not merely that the arts, social sciences and humanities have become less prestigious in the new setting. What Adorno helps us to see is that they harbor an idea of education which is simply incompatible with neoliberal assumptions. The difference turns on how education engages the self. Neoliberal education takes the self with its desires, interests, and assumptions, for granted, and seeks to inflate it with educational capital which can be then be converted into economic, social or cultural capital. An education in spirit, by contrast, transforms the private self into a public or social self by allowing students to wrestle with the social forces at the heart of supposedly private and individualized identities. It cannot achieve this, of course, simply by dispensing the right information about society and its causal properties. This is where Adorno’s insights in opposition to the reification of knowledge through disciplinary specialization are invaluable. An education in spirit is resolutely opposed to the rampant standardization and measurement of knowledge that has become second nature in today’s neoliberal structures of audit and accountability; it is only really possible if teachers and students can risk the possibility of going wrong. Adorno constantly talks of the importance of risk, of giving oneself to the object without reserve, but also without guarantee of success. All of that talk is vitally important in this context, because the type of critical reflection on society at which spiritual education aims can only succeed by engaging the student in risky and non-standardized forms of thinking. Its fruits are the sudden moments of illumination that arise, for Adorno, when the most intimately familiar and the most theoretically abstract fuse in an instant. Those moments cannot be planned and standardized, since they depend, each time, on an unrepeatable conjunction of singular experience and theoretical insight. We can think of these moments as the paradigm forms of the discovery of the social totality at the heart of the self.

I think Giroux is right to see civic illiteracy as a deliberately engineered incapacity of thinking. Its prevalence today has gone hand in hand with the decline in funding and prestige for the humanities and social sciences in the academic world. The education of spirit is an education in public citizenship, preparing citizens to assume the public and social responsibilities of that role by giving them the tools to understand the social relationships at the heart of individual existence. In the neoliberal world in which we are all consumers, there is simply no place for an education in citizenship.